The grown-up man’s genome is quick to be completely sequenced from stays tracked down in the antiquated city

Scientists have long attempted — and fizzled — to grouping the total genome of somebody who kicked the bucket in Pompeii.

The picture of the annihilation of the Roman port city of Pompeii in 79 C.E. by the volcanic debris of Mount Vesuvius is one that probably torment the brain of any works of art understudy. Its destiny was grub for alarming depictions of death and hopelessness, and since the city’s remnants were found in the sixteenth hundred years, its frightfully protected individuals have roused dread and interest. They’ve been the subject of enraged concentrate from that point onward — and some way or another, scientists and people in general are as yet enraptured by protected Pompeiians hundreds of years after the fact.

Presently, interestingly, specialists have completely sequenced the total DNA of a Pompeiian, offering an inside perspective on one individual who passed on in the ejection’s fallout.

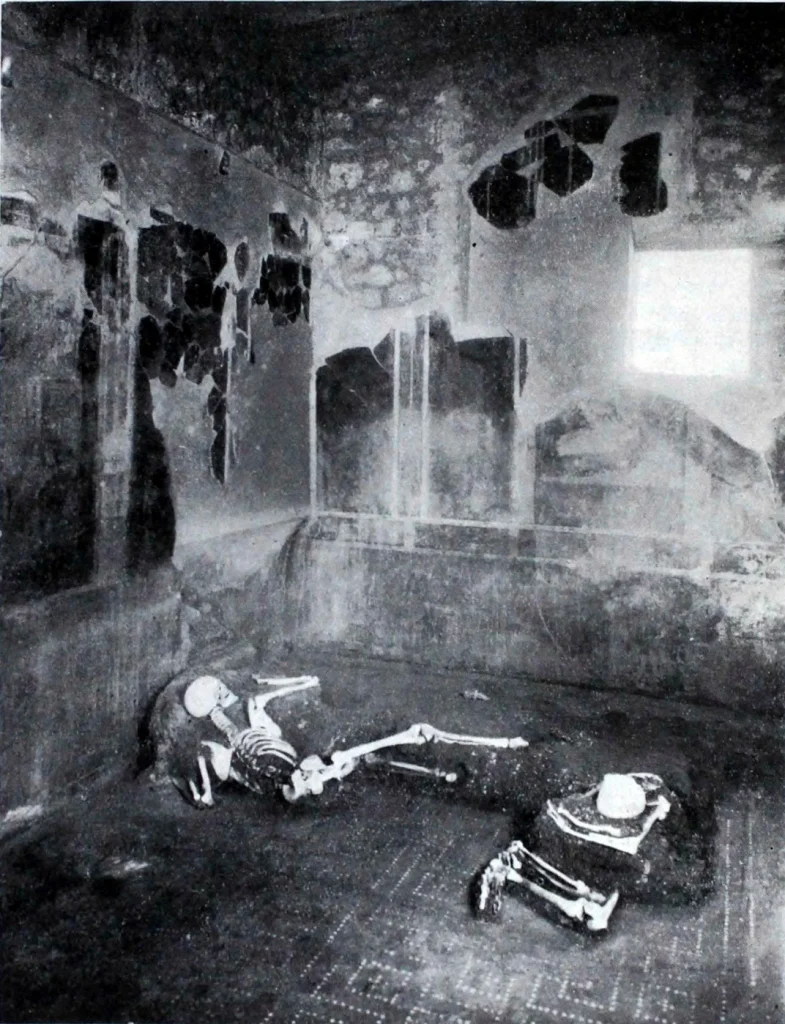

Another review distributed Thursday in Scientific Reports gives more detail on the complex hereditary make-up of a Pompeiian man. Scholastics dissected petrous bones situated at the foundation of the skull of two arrangements of stays found in the Casa del Fabbro, or House of the Craftsman. The bones had a place with a 5-foot-4 man in his late 30s or mid 40s and a lady north of 50 years of age around five feet in level. DNA removed from the female’s bones didn’t give adequate data for a full investigation.

The two bodies were found lying on a triclinium eating space in what was logical the home’s lounge area. Like others in Pompeii, they were approaching their regular routines when everything went horribly wrong. As a matter of fact, the review’s writers compose, the greater part of “people found in Pompeii kicked the bucket inside their homes, demonstrating an aggregate ignorance of the chance of a volcanic emission or that the gamble was made light of because of the moderately normal land quakes in the locale.”

Further testing showed the man probably had spinal tuberculosis. Getting through reports of Rome propose the sickness was a typical difficulty at that point.

However researchers had attempted to arrangement Pompeiian DNA previously, past endeavors to concentrate on more than little strands fizzled. This time, they succeeded — yet given the concentrate’s little example size and the way that the lady’s DNA couldn’t be examined, it’s hazy the way in which comparative examination could passage later on.

Analysts presently desire to utilize the method on other remaining parts. Serena Viva, an anthropologist at the University of Salento and one of the review’s co-creators, tells the Guardian’s Angela Giuffrida the work addresses the longstanding inquiry regarding whether sequencing whole Pompeiian genomes is conceivable.

“Later on, a lot additional genomes from Pompeii can be considered,” she says. “The survivors of Pompeii encountered a characteristic calamity, a warm shock, and it was not realized that you could save their hereditary material. This study gives this affirmation, and that new innovation on hereditary examination permits us to arrangement genomes likewise on harmed material.”

Amusingly, the way Pompeii’s occupants kicked the bucket may really have made their DNA more salvageable, the review’s creators state. They say the pyroclastic materials delivered during the volcanic blast might have in fact “safeguarded” bones “from ecological variables that debase DNA.”

“One of the principal drivers of DNA corruption is oxygen (the other being water),” composed Gabriele Scorrano, an associate teacher at the University of Copenhagen and the review’s lead creator, in an email to CNN’s Sana Noor Haq. “Temperature works more as an impetus, accelerating the cycle. In this way, on the off chance that low oxygen is available, there is a constraint of the amount DNA corruption can happen.”

While new exploration might uncover how rich Pompeiians’ lives were, stories from 79 C.E. show exactly the way that shocking and abrupt their passing truly was.

Roman writer and chairman Pliny the Younger’s nerve racking letters about the fountain of liquid magma’s abrupt emission actually leave present day perusers with a thought of the occasion’s shock. His uncle, prestigious naval commander Pliny the Elder, would die afterward.

“Certain individuals were so scared of passing on that they really petitioned God for death,” Pliny the Younger composed. “Many asked for the assistance of the divine beings, however significantly more envisioned that there were no divine beings left and that the last timeless night had fallen on the world.”

From the outcomes, specialists discovered that the Pompeiian man had a hereditary profile steady with the focal Italian populace of the Roman Imperial Age. His progenitors probably came to Italy from Anatolia, or Asia Minor, during the Neolithic Age.

“That’s what our discoveries recommend, in spite of the broad association among Rome and other Mediterranean populaces, a recognizable level of hereditary homogeneity exists in the Italian promontory around then,” compose the review’s creators.